Why did unionization decline in Minnesota?

By Max Nesterak, Minnesota Reformer

Unions are enjoying the most robust public support in nearly six decades and winning double digit pay raises for their members, yet the share of the American workforce that is unionized remains stuck at historic lows.

In Minnesota, union membership ticked down nearly a full percentage point from 14.2% to 13.3% in 2023, inching closer to the national average of 10%.

The year-to-year dip doesn’t reflect a significant loss for unions, according to labor experts.

The decline could be explained by imprecise data — the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ sample size of Minnesota workers is relatively small. The BLS data on worker union membership, for instance, shows the overall number of Minnesota workers declined .8% in Minnesota last year, while the agency’s more accurate survey of employers reports the number of jobs increased 2%, according to Aaron Sojourner, a labor economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute.

Strong job gains in the economy may also be partly responsible for the apparent decline. Job gains in the private sector are mostly non-union, which dilutes union gains.

Jamie Gulley, president of SEIU Healthcare Minnesota & Iowa, also pointed out that the data only counts workers who are covered by a collective bargaining agreement — many workers who have successfully unionized in recent years don’t yet have one.

For example, the roughly 430 workers at Planned Parenthood North Central States who voted to join Gulley’s union in 2022 wouldn’t be counted because they only agreed to a first contract this month. Neither would any Starbucks baristas since no store has won a first contract despite thousands voting to unionize across the country.

Gulley also sees some good news in the data: The share of workers who are union members ticked up among those who are covered by union contracts, even though government workers aren’t required to be dues-paying members of the unions since the 2018 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Janus v. AFSCME. In Minnesota, roughly 94% of workers covered by union contracts are also union members.

“Which to me shows a really good job by the public sector unions in Minnesota post-Janus in improving their membership rates and loyalty,” Gulley said.

In a broader historical context, however, it’s hard to paint a rosy picture of union membership rates.

Four decades ago, the union membership rate was twice what it is today: Roughly 20% of the American workforce — 17.7 million people — were members of a union in 1983, the first year comparable BLS data is available. Other data show union density was as high as 33% in 1945.

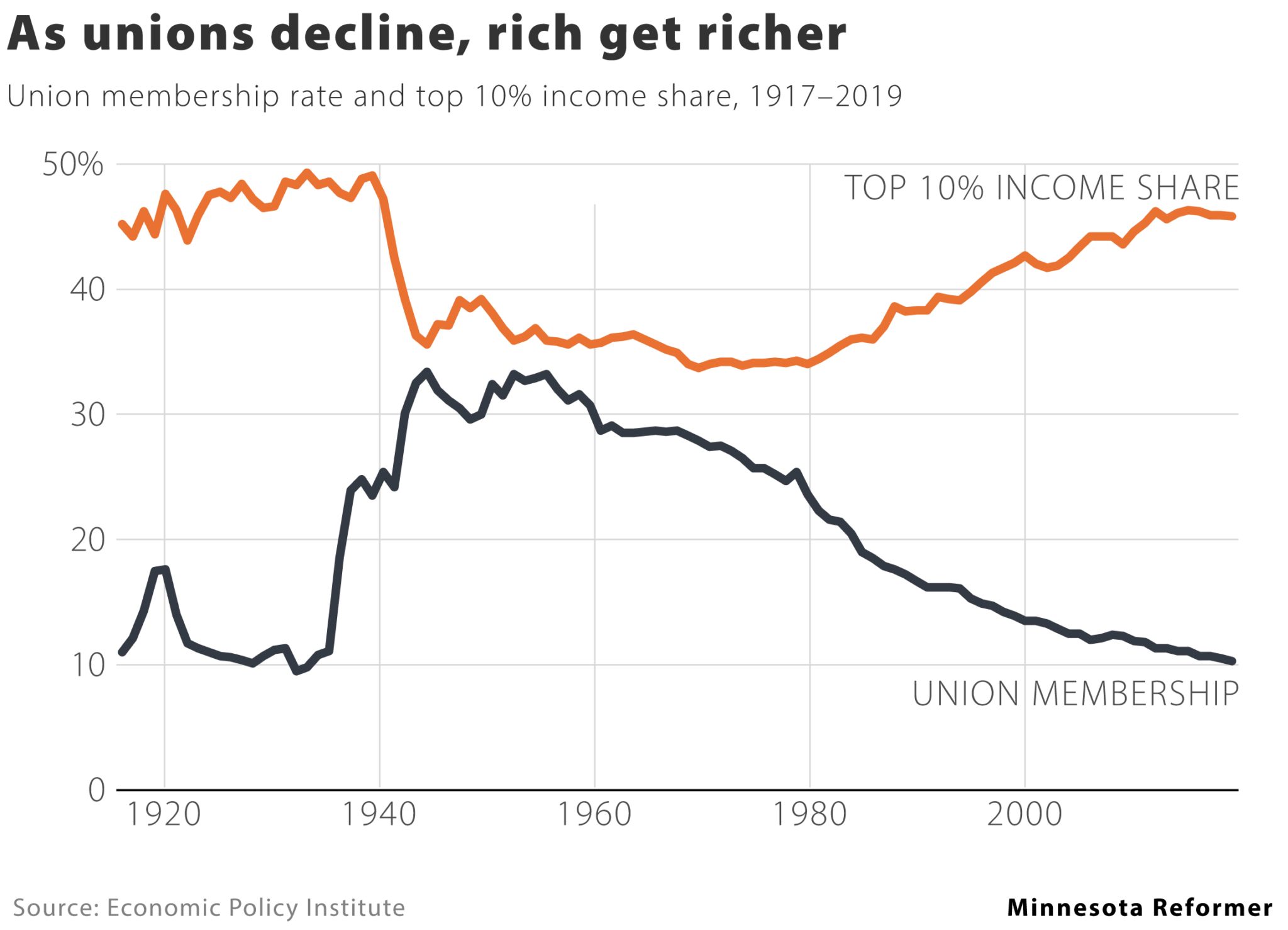

The decline of union power since the 1980s has coincided with stagnating wages in many sectors and a rise in economic inequality, now higher than it’s ever been since the Great Depression. Research by the progressive Economic Policy Institute shows union workers earn about 10.2% more in hourly wages, while nonunion workers benefit in highly unionized industries.

Non-union automakers including Toyota, Hyundai, Subaru and Nissan all raised wages after United Auto Workers struck at Ford, General Motors and Stellantis for over a month to win a 25% wage increase.

The past several decades have not been kind to unions, an era ushered in by President Ronald Reagan in 1981 when he fired striking air traffic controllers: corporate America saw it as a green light to hire strike replacements, and more broadly, take the fight to unions. Democrats also hastened unions’ decline with neoliberal free-trade policies that hollowed out domestic manufacturing as the economy shifted from goods to services.

Corporations also shifted investments from the unionized Rust Belt to southern states without traditions of unionizing, as well as “right-to-work” laws that prohibit unions from requiring dues from all workers covered by their contracts.

Unions also struggled to meet the moment: Some unions were plagued by corruption, which repulsed workers and supported anti-union talking points. Some labor leaders also say large unions became complacent, focusing more on defending their members’ benefits than organizing new workers. Others say unions have alienated their members with their political activism and lost connection to their members’ needs.

Yet coming back will require more than just organizing more workplaces, one Starbucks store at a time. It requires a change in law, according to union leaders.

“Labor movement growth is historically almost always related to what the rules are,” Gulley said. “In the 1930s … rules were written to allow people to organize, that made organizing easy and simple. That’s when people join the union.”

Since the National Labor Relations Act passed in 1935, however, Congress and the courts have generally made it harder to organize and easier for companies to influence union elections. Companies can break the law while risking little in the way of financial penalties, chalking it up to the cost of doing business. The National Labor Relations Board, which oversees private sector unions, cannot issue civil fines to companies for violating the law.

“We treat employers and management the way we treat 5-year-old children who just stole something for the first time. We say, ‘Give back what you stole and say you’re sorry,’” Sojourner said. “That’s an appropriate remedy the first time somebody breaks a rule … but it’s a completely dysfunctional policy for leaders who make strategic choices to boost their own pay at the expense of employees’ rights.”

President Joe Biden has championed the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would make it easier for workers to organize and harder for companies to break the law. The proposal has floundered in a sharply divided Congress. Since the 1970s, every time Democrats have had control of the presidency, the House and a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, they’ve failed to rewrite labor law in favor of unions, as the American Prospect’s Harold Meyerson recently noted.

Labor unions don’t need to wait on Congress, however. Democrats in control of the Minnesota Legislature passed a slew of worker-friendly legislation, including a ban on so-called “captive audience meetings,” during which employers require workers to listen to presentations about why unions are bad for them.

SEIU Healthcare Minnesota & Iowa has seen the fastest growth of any union in Minnesota over the past decade, tripling its membership under Gulley’s leadership from 14,500 workers in 2012 to 55,000 today — in part through changing the rules.

SEIU led a yearslong effort to pressure Minnesota lawmakers to allow tens of thousands of personal care attendants to unionize. The law was changed in 2013, and workers voted to unionize the following year. Since then, the union has pushed up wages for home care workers from $9 an hour in 2015 to $19 an hour today.

If more states allowed home care workers to unionize, that could bring millions of workers into collective bargaining agreements. Gulley also sees a path toward significant labor growth in allowing gig workers to unionize, and allowing workers to organize entire industries. SEIU successfully lobbied for the creation of a nursing home standards board last year, which will set minimum pay and benefits for thousands of union and non-union nursing home workers alike.

“You’ve just got whole swathes of the country that don’t have bargaining rights,” Gulley said. “If the rules are there, you will see the growth.”

Minnesota Reformer is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Minnesota Reformer maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Patrick Coolican for questions: info@minnesotareformer.com. Follow Minnesota Reformer on Facebook and Twitter.

Member discussion