Four years after George Floyd, Minnesota’s racial gaps remain stark

By Christopher Ingraham

Four years ago this week, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd. The event was captured on video, inspiring protests and riots in Minnesota and beyond.

Floyd’s killing brought newfound attention to Minnesota’s longstanding racial disparities, some of the nation’s worst. In the days following Floyd’s death, politicians and business leaders vowed to reckon with the state’s history of systemic racism and find ways to address it.

Gov. Tim Walz, for instance, said “this is probably our last shot, as a state and as a nation, to fix this systemic issue.” The Minnesota House declared racism a public health crisis and promised to address the “disparities in family stability, health and mental wellness, education, employment, economic development, public safety, criminal justice, and housing” created by racism.

The city of Minneapolis created a truth and reconciliation commission to tackle racial inequities, while major state businesses including Target, 3M and Xcel Energy pledged “to do more to eliminate racial disparities because our state’s future depends on it.”

Upon winning control of both legislative chambers and the governor’s mansion in 2023, the Democratic Farmer-Labor party also passed a number of bills meant to boost the fortunes of low-income Minnesotans across the board. They included tax credits for working families and their children, one-time tax rebates for families earning less than $150,000 a year, and over $1 billion in funding to nonprofits, including many working to address racial and economic disparities.

But those disparities have proven difficult stubborn. A Reformer analysis finds that gaps have narrowed modestly on some key socioeconomic indicators like income and educational attainment. But in other areas of concern, especially the so-called deaths of despair thought to be indicative of major social breakdown, Minnesota’s racial gaps have widened considerably.

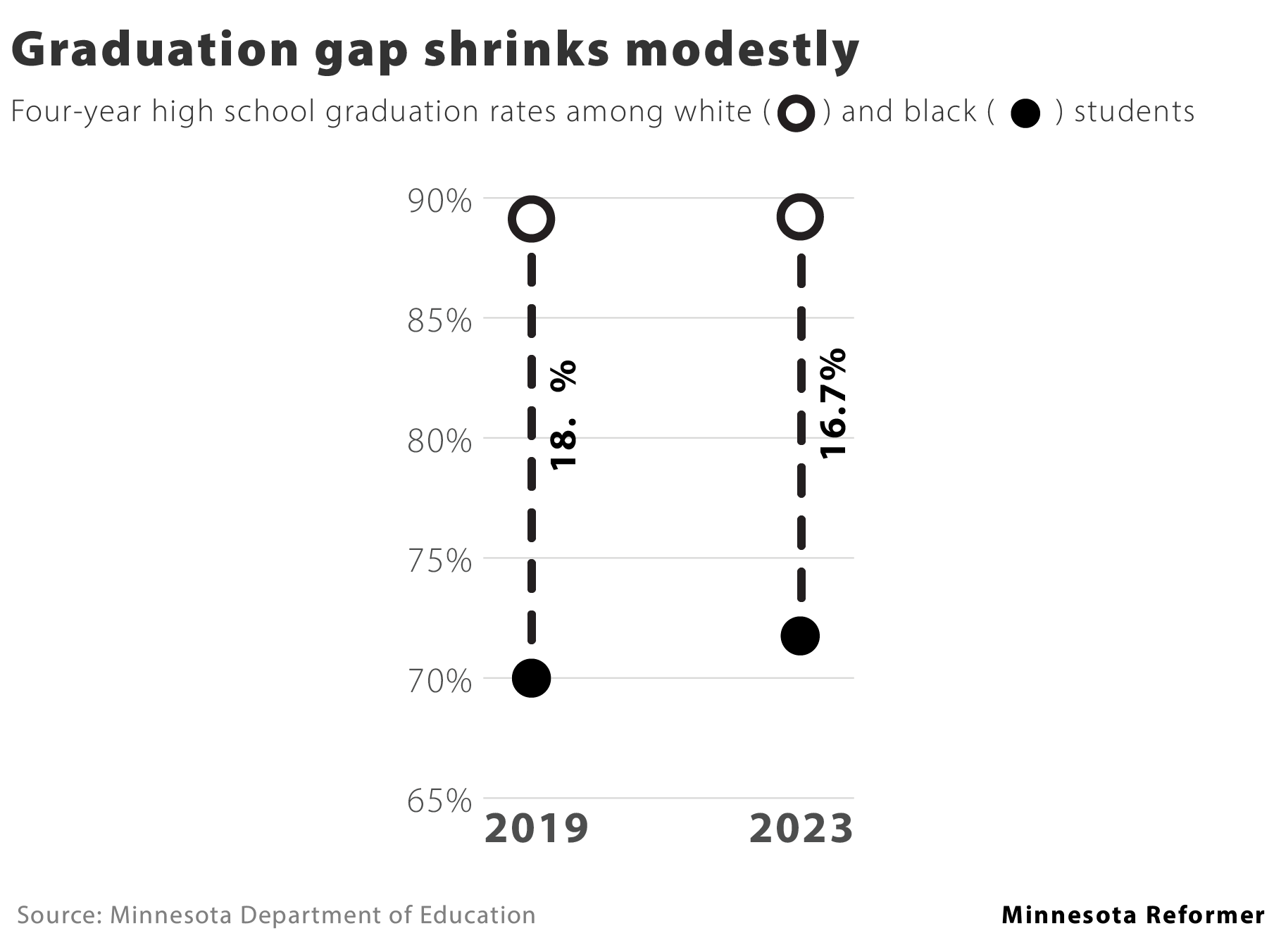

Education

In 2023, about 72% of Black Minnesota public school students graduated within four years, compared to 89% of whites. That 17 percentage point gap is two points smaller than the racial graduation gap in 2019, the year prior to the pandemic and George Floyd’s killing. The shrinking gap was driven mainly by an uptick in Black students’ graduation rate.

Income

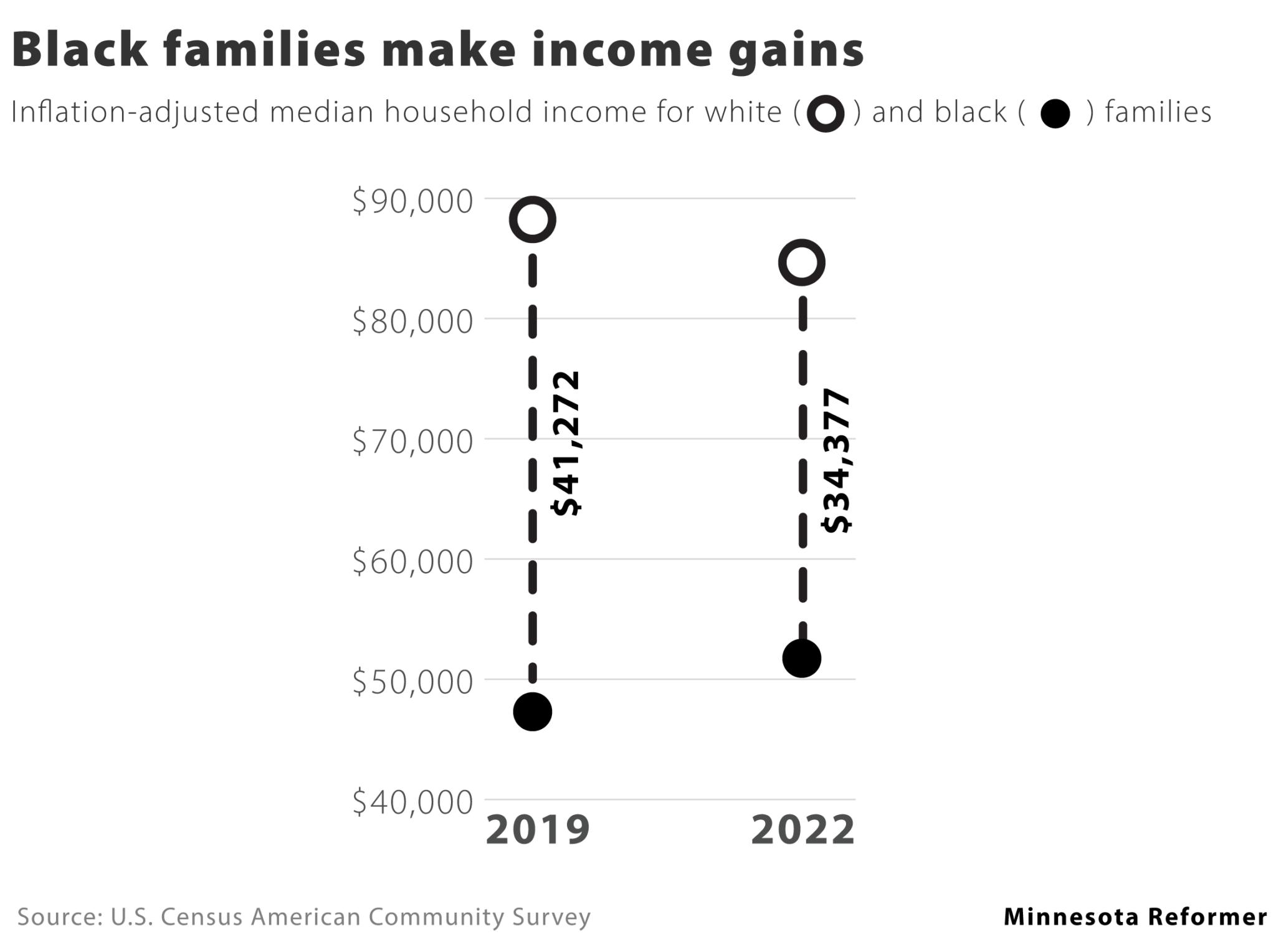

Between historic job losses, infusions of government aid and a volatile inflationary environment in the years following, the pandemic represented a massive disruption to American incomes. As of 2022, the most recent year with comparable data, Census data show that Minnesota’s Black-white income gap shrunk by about $7,000 inflation-adjusted dollars since 2019.

That reduction was partly due to Black income gains, as well as to white income losses once inflation is factored in. Currently the typical white household brings in about $35,000 more annually than the median Black family.

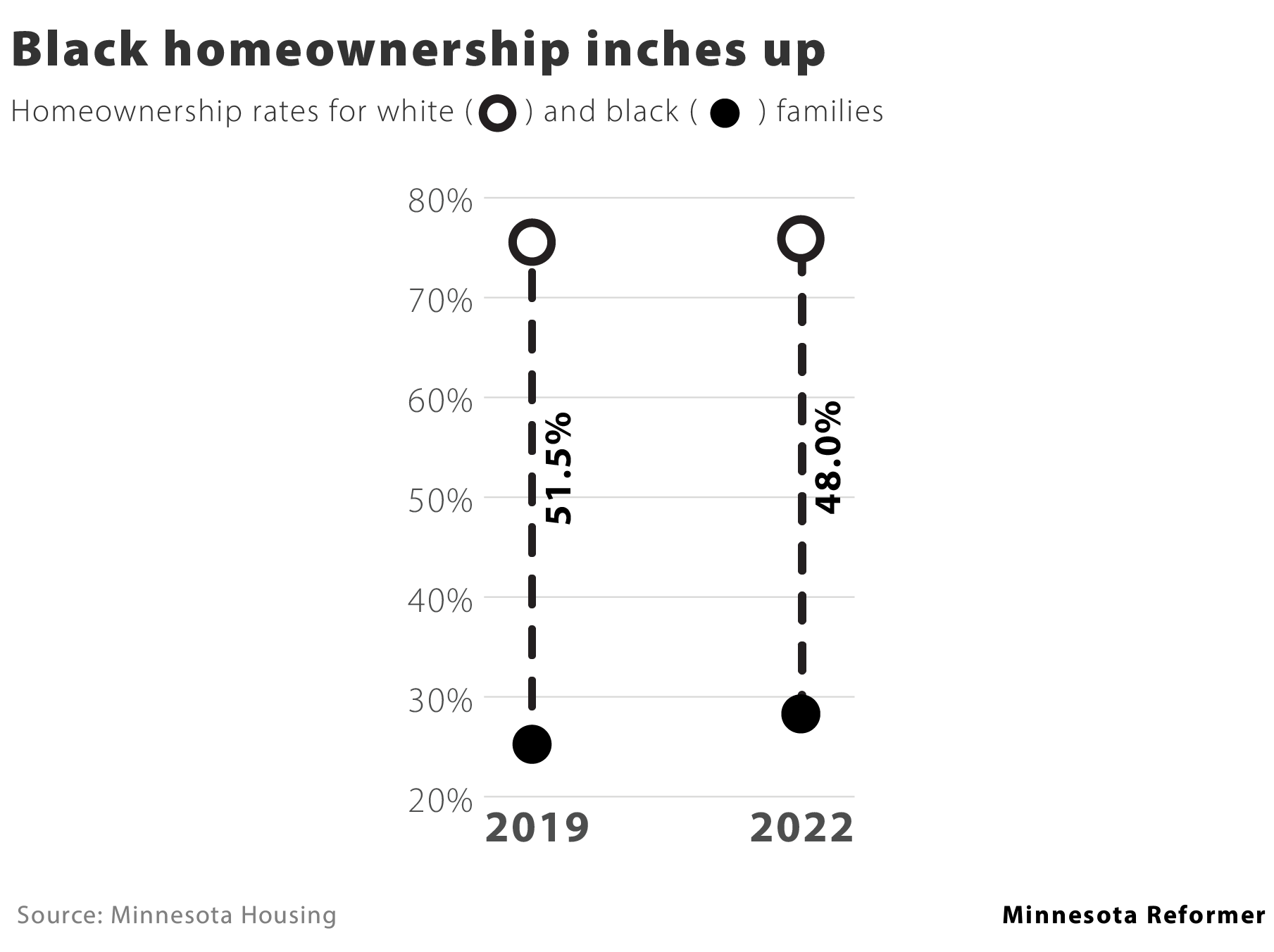

Homeownership

The homeownership gap between Blacks and whites shrunk only modestly between 2019 and 2022, according to data from Minnesota Housing. Home values are the major engine of middle-class wealth, and the low homeownership rate among Black families means many are effectively locked out of building the type of nest egg that can provide a level of financial stability across several generations.

Low-level arrests

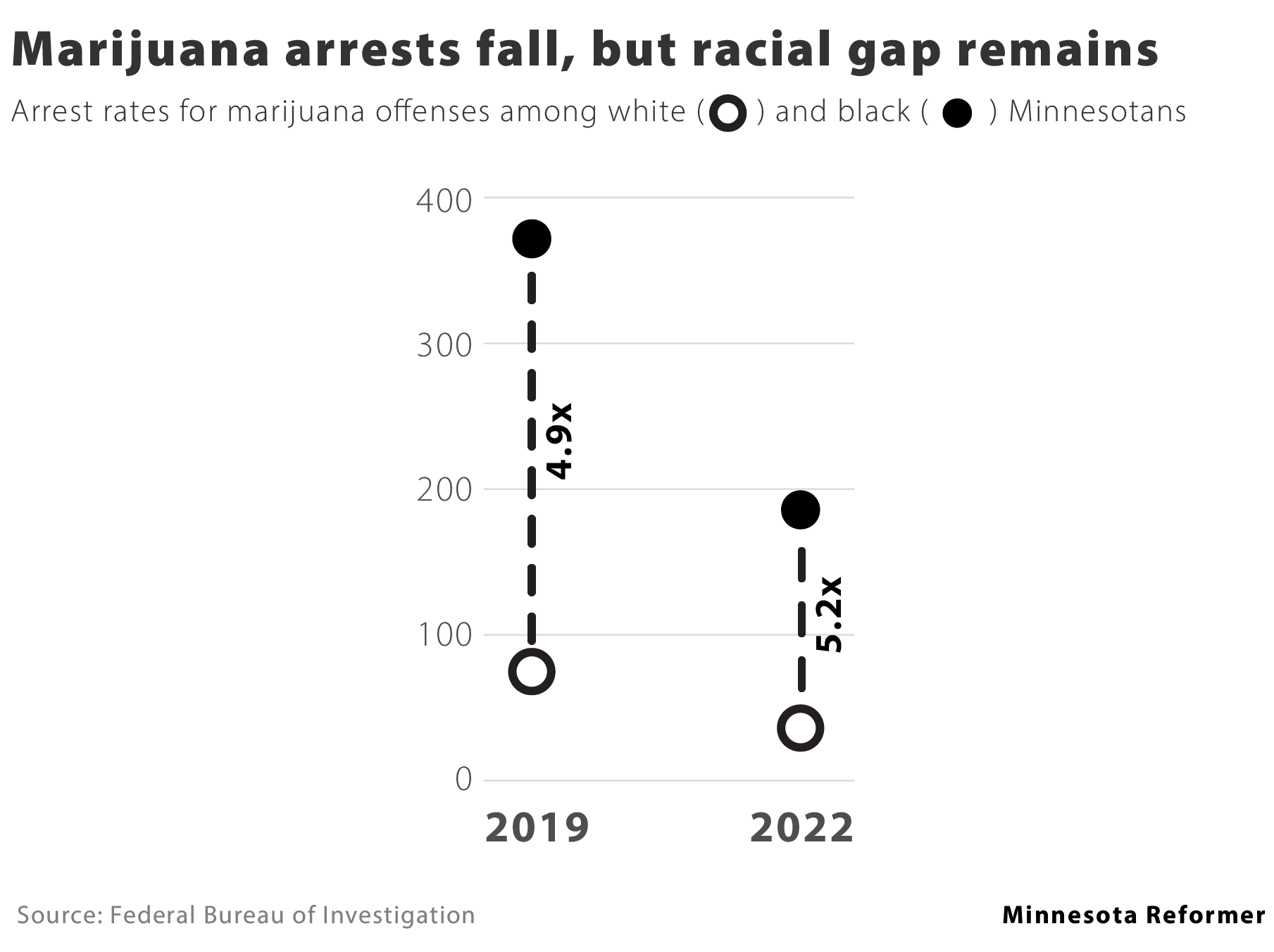

Marijuana arrests are a useful proxy for the intensity of policing in a community. In Minnesota, those arrests plummeted across the board between 2019 and 2022, according to FBI data, owing in large part to the state’s legalization of marijuana edibles in the latter year.

While arrests fell, disparities in marijuana policing remain. Black Minnesotans were 4.9 times more likely than whites to be arrested for pot in 2019, and 5.2 times more likely in 2022. National data show that Black and white Americans use marijuana at similar rates.

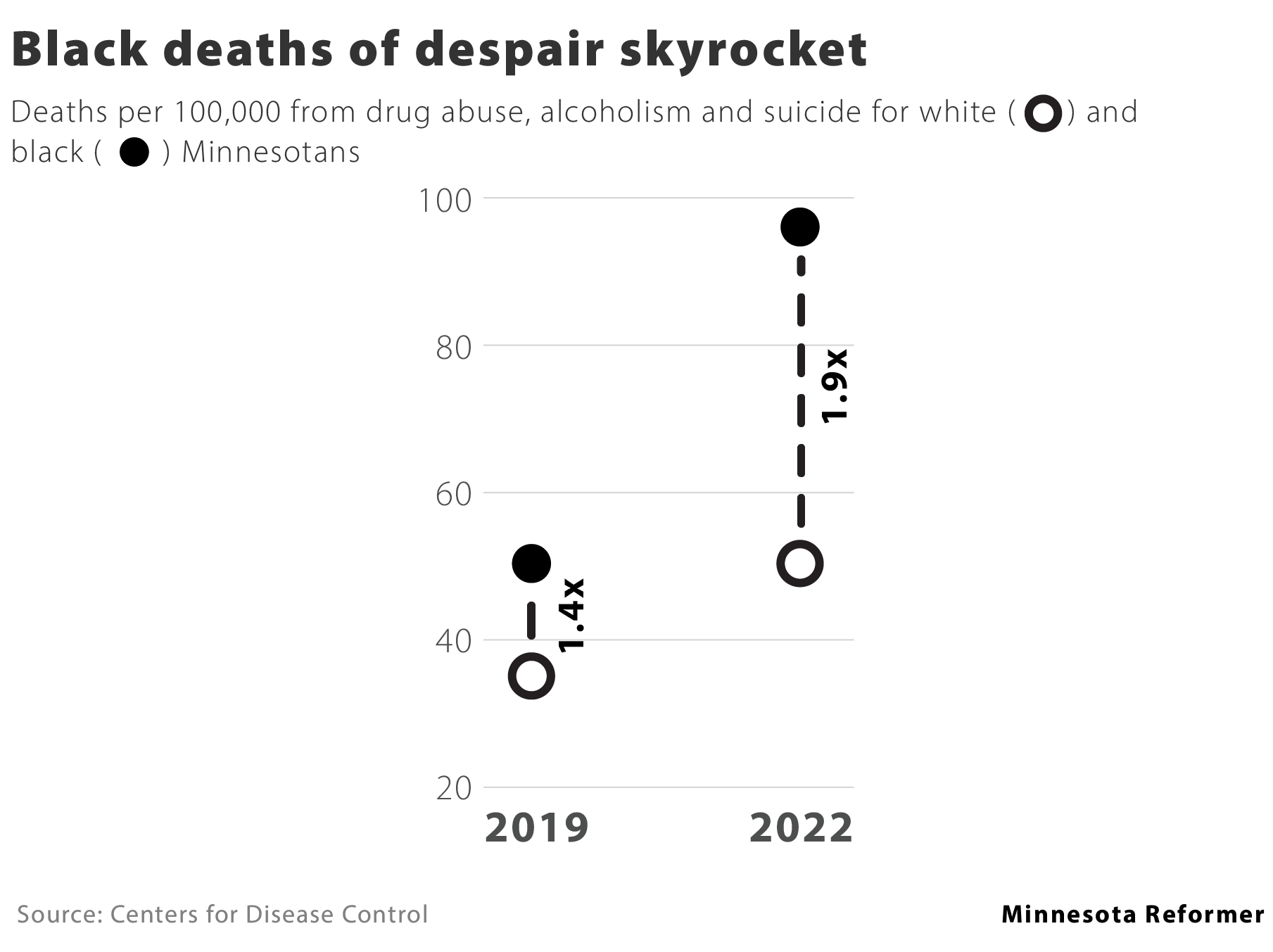

Deaths of despair

Deaths from alcohol, drug use and suicide are largely associated with rural white populations. However in recent years those deaths have skyrocketed among Black Americans.

In 2019, a Black Minnesotan was about 40% more likely than a white one to die from alcoholism, drug abuse or suicide. While deaths of despair rose among both populations during the pandemic, the increase was much steeper for Black Minnesotans.

Today, a Black Minnesotan is nearly twice as likely to die of those causes. If the popular narrative surrounding deaths of despair — that they’re a sign of working-class immiseration and desperation — is correct, this suggests that the racial reckoning envisioned by civic leaders in the wake of George Floyd’s death is still a long way off.

Minnesota Reformer is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Minnesota Reformer maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor J. Patrick Coolican for questions: info@minnesotareformer.com. Follow Minnesota Reformer on Facebook and Twitter.

Member discussion